Ancient Egyptian kings loved to portray themselves bashing someone else’s head in.

One of the most famous head-basher kings is Narmer, often considered to be the first ruler of a unified Egypt, perhaps a bit earlier than 3000 BCE. On the Narmer Palette King Narmer is shown holding his victim by the hair. His other arm is held high, ready to bring down his stone mace and batter him to death. His face is serene - it's just another ordinary day.

A willingness to resort to violence to get your own way seems to be an essential element of kingly power. But if this is an essential feature, why did anyone put up with it in the first place? A king getting his way means someone else loses out - and why would anyone want to subject themselves to a bully?

Great Kingdoms of Africa edited by John Parker explores this question (among others) in a collection of nine essays, each covering a different kingdom in African history. In the first essay - Ancient Egypt and Nubia: Kings of Flood and Kings of Rain David Wengrow sketches out an answer.

On the open road

The people of ancient Egypt and Nubia (i.e. modern Sudan) were originally pretty similar. They moved around a lot, herded cattle, liked to keep their hair neat and make themselves look good, with “a dazzling array of beadwork, combs, bangles and other ornaments made of ivory and bone” found in graves all the way up and down the Nile.

But in the late fourth millennium BCE (i.e. from 4000 to 3000 BCE) the Egyptians and the Nubians started to go their separate ways. This was caused by a big shift in the climate. The summer monsoon rains that had once fallen all over Egypt moved further and further south, turning the country into a year-round desert.

Prisoners of climatography

Whereas previously the people of Egypt had been able to follow the grasses and wander around all over the place, with their herds of cows to sustain them, they were now squashed into a thin strip of land a few kilometres either side of the Nile.

This meant that when a violent sociopath with a stone mace slung over his shoulder (and a posse of like-minded desperadoes at his back) turned up at your door demanding that you hand over a significant proportion of your harvest, you had nowhere to run. In choosing between fight, flight or submit, submission was the only viable option - vivat rex Narmer!

As Wengrow puts it:

The real puzzle of Nubia’s ancient history... is not whether it developed states or empires like those of neighbouring pharaonic Egypt. Rather, it is how its population managed to prevent the emergence of similar forms of domination in their own midst, despite the existence of Egyptian models of governance on their doorstep and the effects of recurring Egyptian predation on their people and resources.

David Wengrow, Great Kingdoms of Africa

Live to herd another day

Turning to Nubia, kingship seems to have been later in developing and with nothing like the system of control in Egypt. Why? Because you weren’t stuck fast to the river like the unfortunate Egyptians, and running away was still an option. A king with no subjects is demoted by default.

Resistance is futile

I suspect I am behind the times here, but prior to reading this book I had always considered the puzzle of political complexity - kings, priests and whatnot - to be: how do you design the system? But Wengrow’s point is the opposite. Given the tendency of humans towards domination, the puzzle is: how do you work to prevent the emergence of such a system?

A kingdom therefore represents the failure of a people to escape oppression. The lack of a kingly structures and / or weak kings represents a great - and deliberate - success story for the ordinary folk.1

Surplus kings

This gave me a new perspective when thinking about the emergence of the other great primordial - and river based - civilisations: the Mesopotamians, the Indus Valleyans, and the Yangtze River folk.2 It may not have been the agricultural surplus that allowed more complex societies but instead the fact that “stuck by the river” farming communities were powerless to flee parasitic proto-kings. In other words, the crop surplus only existed because its creation was demanded - at the point of a spear, or the blunt end of a stone mace.

I should stress that these are my musings only and not those of the authors who would likely be horrified at my mono-causal tendencies. But it is their fault for planting the idea in my head 🙂.

Coercion and consent

The idea here is that the king maintains power by coercion - he wants what you have and you are powerless to resist. But Great Kingdoms of Africa also explores the idea of consent - where you are happy to give up the fruits of your labour.

Many if not all of the kingdoms in the book (and everywhere else in the world) endowed their king with some sort of sacred role. So we hear of great Zulu festivals where a great vomiting-on-a-snake-model ritual was designed to boost “mystical powers of rejuvenating and protecting the king and the nation, and of gathering the people together in loyalty to the king.”

I think the idea is that if you are doing what a priest-figure tells you this is consent, if you do what a soldier-type tells you this is coercion.3

One of the key themes of the book is that there is a mixture of different strategies of kingship - and strategies of subjectship - across different kingdoms. Despite what you might imply from the title of the book there is no one archetype of an African Kingdom.

What’s in the book?

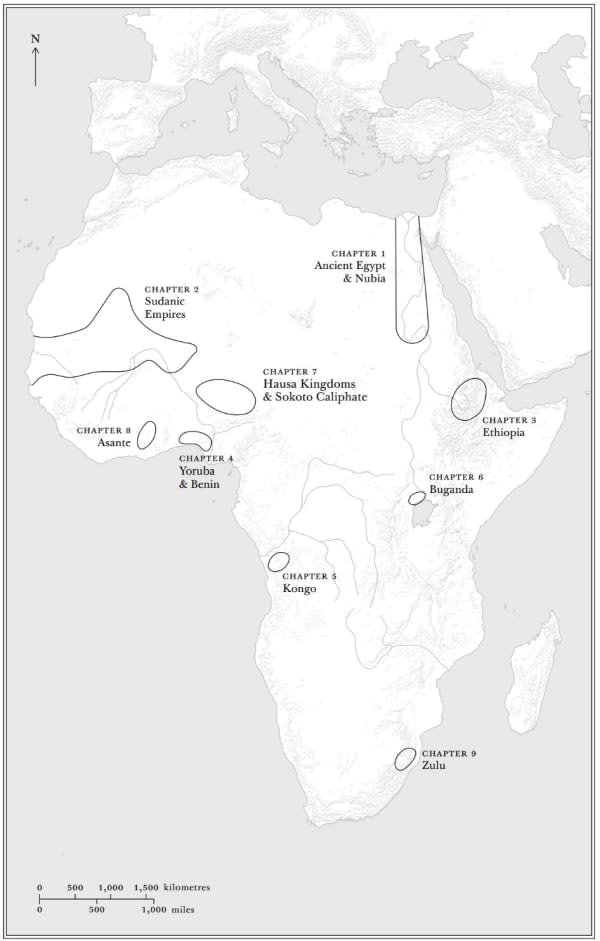

Each essay in the book is about 20 to 30 pages long, on kingdoms across Africa covering the modern countries (and previous kingdoms) of:

- Egypt and Sudan (Ancient Egypt and Nubia)

- Mali and Senegal (Sudanic Empires)

- Ethiopia (Solomonic Kingdom)

- Nigeria (Yoruba and Benin)

- The Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola (Kongo)

- Uganda (Buganda)

- Nigeria again (Hausa to Sokoto)

- Ghana (Asante)

- South Africa (Zulu)

This is most easily grasped by looking at one the excellent maps from the book, reproduced below:

Map of Africa showing the the kingdoms featured in Great Kingdoms of Africa by Matthew Young, © Thames & Hudson

By focusing on iconic rulers and kingdoms, mostly before their contact with European powers, and covering more or less the whole continent Great Kingdoms of Africa becomes an important work in enlightening those of us, like myself, who are mostly ignorant of most of African history.

It is also an excellently presented book, with loads of well chosen colour pictures, some brilliantly designed maps, and the whole thing comprehensively indexed.

Caveat lector

There is a major caveat though. While the subject matter is fascinating, and the ideas discussed important, the writing itself does not sit lightly on the page - it can be quite hard work to plough through many of the essays, which often come across as dryly academic in tone.

Here is a typical sentence to give you a flavour:

He [Zara Yaqob, an important Ethiopian king] invented a new model for Church-state relations, in which the secular state was the dominant force, creating an indigenous absolutism based upon the concept of Solomonic legitimacy. He reformed the Church in ways that unified the country, thereby further consolidating royal power.

Great Kingdoms of Africa, Essay on The Solomonic Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia

Passages like this leave me convinced of the academic respectability of the authors but none-the-wiser myself on what it really all means.

Who is it for?

So I am left a bit unsure who Great Kingdoms of Africa is aimed at. An academic specialist will probably already know all this stuff. But a lay person would expect something a bit less dry to properly whet their appetite.

I suspect that part of this reader-writer mismatch that I experienced is due to the fact that the authors are keen to go beyond the typical account of African kingdoms, and also air some of the current scholarly debates. But given that I would put myself at the Usborne lift-the-flap level when it comes to African history, much of the nuance and careful language went over my head.

The upshot is that I wouldn’t read this book on the expectation that you will be entertained.

But I would consider reading it if you want to be educated and you are willing to put in some hard graft getting to the bottom of it all.

Conclusion

Great Kingdoms of Africa will give you a great insight into the breadth and depth of African history - in particular the history before Europeans arrived on the scene. But you may find yourself floundering in the deep end as you try to wade through the scholarly prose.

This glosses over the role that kings might play in restraining lesser or alternative bullies such as aristocrats and soldiers, but I like it as way of thinking about the early emergence of kingship. ↩︎

Maybe also the American civilisations? I’m not sure enough about their origins to include them in my speculation. ↩︎

The idea of obeying by consent is not always clear cut. For example, my kids (age four and seven) might consent to do things I ask / tell them to do. But how much would they do so if I was smaller and weaker than they are? ↩︎

Book details

(back to top)- Title -

Great Kingdoms of Africa

- Author -

John Parker

- Publication date -

March 2023

- Publisher -

Thames and Hudson Ltd

- Pages -

336

- ISBN 13 -

9780500252529

- Podcast episode -

Leonard Lopate at Large on WBAI Radio in New York: John Parker on Great Kingdoms of Africa

- Podcast episode -

- Amazon UK -

- Amazon US -