These half civilised governments such as those in China Portugal and Spanish America all require a Dressing every eight or Ten years to keep them in order... They care little for words and they must not only see the Stick but actually feel it on their Shoulders.

Viscount Palmerston as UK foreign secretary, 1850

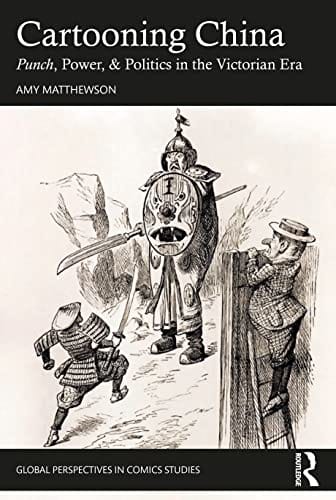

Amy Matthewson recounts this belligerent statement in her new book: Cartooning China: Punch, Power, and Politics in the Victorian Era.

Palmerston - one of the most well known British politicians of the 19th Century - had ample opportunity to practice what he preached, invading, attacking or menacing a wide variety of countries all over the world.

One of which was China...

Held to ransom

In 1856 a ship called the Arrow was seized by the local Chinese governor in Canton harbour, who suspected its (Chinese) crew of piracy. The (British) captain of the ship - who was lunching with a friend on another boat at the time - complained to the local British official who responded by demanding a release of the (possible) pirates and an apology. They got the first but not the second and responded by bombarding Canton from the sea.

Back in the UK people were divided on what to do. Was it the local British official’s fault for escalating a relatively trivial incident into armed conflict? Or... was it the Chinese governor's fault for his general obstinacy in the face of the militarily - and morally - superior British?

(Election) victory at any cost

Pam himself had no doubts, painting the doubters who refused to support the Brits abroad as un-patriotic and un-English. So out came the Stick: 15,000 British and French troops who won a few battles, marched to Peking (Beijing), forced the Chinese government to sign a harsh and punitive treaty, and destroyed the emperor’s summer palace. Meanwhile back in the UK Palmerston won a general election with a landslide victory, which of course was the point all along.

This invasion has become known as the Second Opium War, because a key reason for fighting it - other than to get an apology for the confiscation of a small boat - was to allow British merchants to trade freely in China, including in opium.

Egging them on

One of the fascinating things about this conflict, and explored by Matthewson in her book, is the role that British public opinion had to play.

Palmerston fought the war in order to showcase his true Brit credentials and win an election. But the righteous British vengeance card only works if your opponent is a cad. To put it another way: if you can convince everyone that the other chaps are the bad guys, well that must make you the good guy1.

The Second Opium War led to a noticeable shift in the British view of the Chinese. After the war opinions were, Matthewson suggests, much more hostile. But this hostility was itself partly the product of this carefully manufactured war.

And the press, including the popular magazine Punch with its eye-catching full page political cartoons, variously shaped, responded to and amplified these views.

The curse of print media

Which raises the interesting question of cause and effect. Why did Britain go to war? Because the Chinese took a small ship registered as British. War was reasonable response, Palmerston tells us, not only because of the ship but because of the generally cruel and untrustworthy behaviour of the Chinese which must be punished. This is confirmed when Britain and France invade China and in fact the Chinese frequently try to kill British and French soldiers, sometimes succeeding in horrible ways. Therefore the war - and certainly the punishment dished out by the British - was a consequence of Chinese brutality.

In the midst of this vicious circle there are papers like the Times and Punch who are in the business of serving up palatable dishes to the public and will happily jump on a pro British / anti Chinese bandwagon, driven by the government - with cartoons such as New Elgin Marbles showing the Chinese emperor as a grotesque semi-human figure in contrast to the upright, stern and noble portrayal of Lord Elgin.

In Cartooning China: Punch, Power, and Politics in the Victorian Era Matthewson - as you might expect from the title - concentrates on the role of the magazine Punch in the portrayals of China and the Chinese.

What’s in the book?

The book is fairly concise at 174 pages with chapters covering:

- The writers and cartoonists who produced Punch.

- The general outlook of the paper and how it changed over time.

- Portrayals of China from 1850 to 1860 covering the Great Exhibition and the Second Opium War referred to above.

- Portrayals of China in the 1890s when under attack from Japan.

The great thing about the book is that it reproduces (I believe) every Punch cartoon referring to China over this period rather than cherry picking favourites. This allows you to draw your own conclusions about how China was perceived at that time in the UK, rather than relying on the author to choose those cartoons which they think are representative.

Also by giving us details of who is writing the magazine and their politics - plus a look at the circulation figures over time - we can make a judgement about how representative they were of British opinion over that time.2

Respectable racism

One of things I was interested to learn for example was that Punch was always intended to be a respectable paper that avoided sensation - ie didn’t print rude cartoons, unlike some of its rivals. The idea was that even the ladys could read it without having to retire blushing to the powder room. This gave it an air of respectability and enabled a wider circulation.

However looking at the cartoons relating to China as a modern reader they are pretty much without exception offensively racist. These two cartoons from Punch in 1857 give you a good idea of what I mean.

When the lady in our household (my wife, who also happens to be Chinese) picks up these Punch illustrations, my feeling is one of slight awkwardness tinged with some shame. Even though - because these cartoons are from an era which has now passed - they don’t really bother her.

Any drawbacks?

Not a drawback as such but I think it is important to point out that this book is a study rather than a story. While the non-academic (for example: me) can get a lot out of it, the writing style is more scholarly than stirring.

My other observation is that the cartoons themselves don’t tend to illustrate the changing views of Punch as much as the written articles in Punch that went alongside them.

For example I was trying to trace the increasingly negative portrayal of China as the Second Opium War started. However the cartoons - to my untrained eye - all seemed similarly negative and dismissive, whether before or after the late 1850s. To really understand what’s going on you have to see what Matthewson brings out from the changing tone of the articles that were published.

My conclusion was that although this is a book about cartoons - and Punch is famous for them - you can’t just skim through it (or Punch) looking at the pictures!

Conclusion

An illuminating work on Victorian British perceptions of China - and Victorian British perceptions of themselves - this is a great little book if you are interested in this area of history.

By focussing on the cartoons in Punch it is a really accessible way to see first hand how British people were shown the rest of the world - which was all too often as Palmerston had said: half civilised and deserving of the stick.

Palmerston’s exact words in describing the Chinese were “a set of kidnapping, murdering, poisoning barbarians”. ↩︎

The wide circulation and multiple readers per copy suggests it was at the very least acceptable to a fairly broad part of society even if it was written by a smaller middle class group of London based men. ↩︎

Book details

(back to top)- Title -

Cartooning China : Punch, Power, & Politics in the Victorian Era

- Author -

Amy Matthewson

- Publication date -

March 2022

- Publisher -

Routledge

- Pages -

174

- ISBN 13 -

978-0367460990

- Amazon UK -

- Amazon US -

Next post

← How to achieve (historical) immortality - on a budget

Last post

New history books in September 2022 →